Guest Curator: Daniel Koehler

“Digital Matter”; “Intelligent Matter”’; “Behavioural Matter”; “Informed Matter”; “Living Matter”, “Feeling Matter”; “Vibrant Matter”; “Mediated Matter”; “Responsive Matter”; “Robotic Matter”; “Self-Organised Matter”; “Ecological Matter”; “Programmable Matter”; “Active Matter”; “Energetic Matter”. There is no term enjoying better reputation in today’s experimental architectural discourse. Gently provided by a myriad of studios hosted in pioneer universities around the world, the previous expressions illustrate the redemption of a notion that has traditionally been dazzled by form’s radiance. After centuries of irrelevance, “Matter” has recently become a decisive term; it illuminates not just the field of experimental architecture, but the whole spectrum of our cultural landscape: several streams in philosophy, art and science have vigorously embraced it, operating under the gravitational field of its holistic and non-binary constitution.

However, another Copernican Revolution is flipping today’s experimental academic architecture from a different flank. In parallel to matter’s redemption and after the labyrinthic continuums characteristic of the ’90s, discreteness claims to be the core of a new formal paradigm. Beside its Promethean vocation and renewed cosmetics, the discrete design model restores the relevance of a term that traditionally has been fundamental in architecture: the notion of part. However, in opposition to previous architectural modulations, part’s current celebration is traversed by a Faustian desire for spatial and ontological agency, which severely precludes any reverential servitude to its whole.

The singular coincidence of matter’s revival on the one side and the discrete turn on the other opens a debate in relation to its possible conflicts and compatibilities in the field of experimental architecture. In this essay, the discussion gravitates around one single statement: the impossibility of a materialist architectural part-thinking. The argument unfolds by approaching a set of questions and analysing the consequences of its possible answers: how matter’s revival contributes to architectural part thinking? Is matter’s revival a mere importation of formal attributes? Which are the requirements for a radical part-thinking in architecture? Is matter well equipped for this endeavour? In short, are the notions of matter and part-thinking compatible in an architectural environment?

Pre-Socratic philosophy defined matter as a formless primordial substratum that constitutes all physical beings. Its irrevocable condition is that of being “ultimate”: matter lies in the depth of reality as more fundamental than any definite thing. Under this umbrella, pre-Socratic philosophy ramifies in two branches: the first one associates matter with continuity, the second one associates matter with discretism.

Anaximander is the standard-bearer of the first type: the world is pre-individual in character and it is fueled by the apeiron, a continuum to which all specific structures can be reduced. We can find traces of this sort of materialism in Gilles Deleuze’s “plane of immanence”, Bruno Latour’s “plasma”, or Jane Bennett’s “vibrant matter”. Democritus is the figurehead of the second type: the world is composed by sets of atoms, that is, privileged discrete physical elements whose distinct combinations constitute the specific entities that populate the world. Resonances of this sort of materialism can be found in the “quanta” of contemporaneous quantum mechanics. Independently of their continuous or discrete nature, both types of materialisms are underpinned by an ontological assumption: the identification of matter with an ultimate cosmic whole. To this purpose, matter’s generic condition is decisive: its lack of specificity is precisely what grants matter the status of “ultimate”, which logically and chronologically precedes distinction.

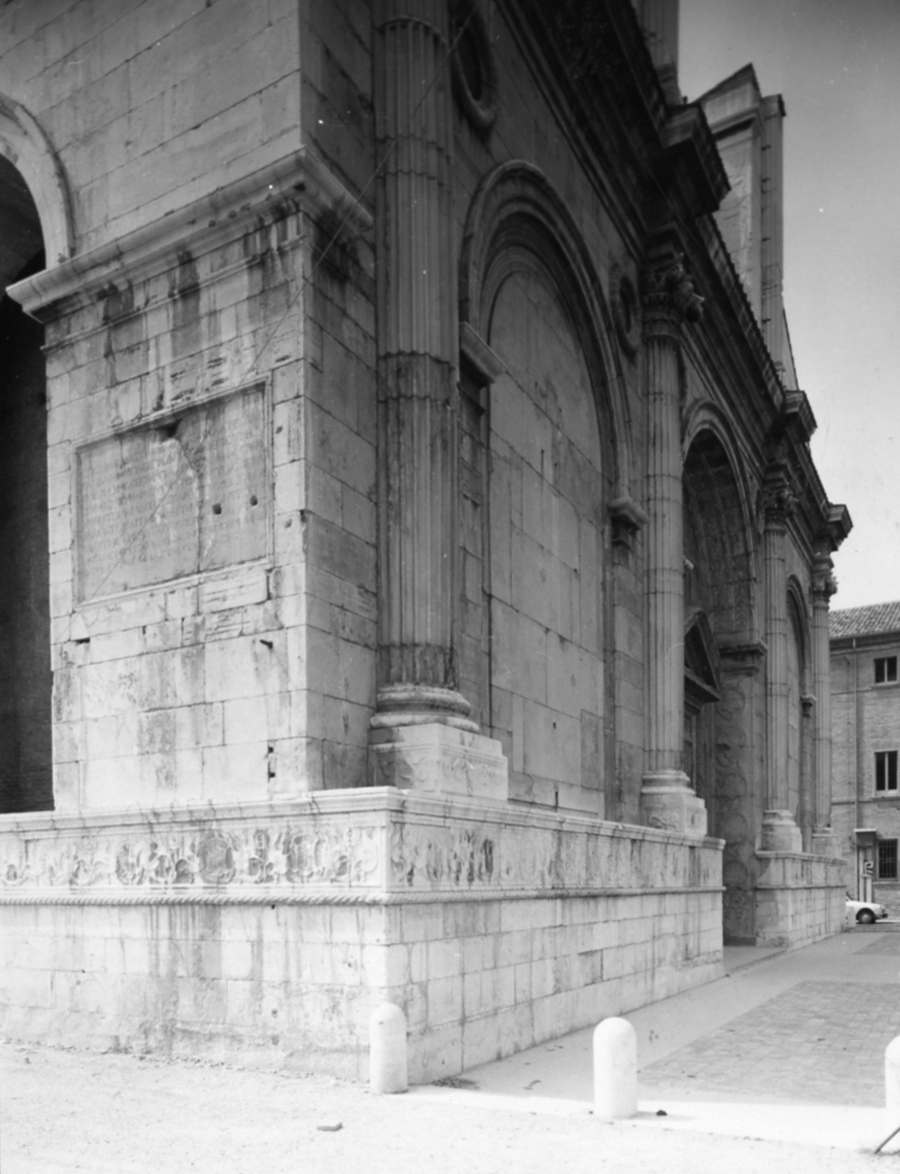

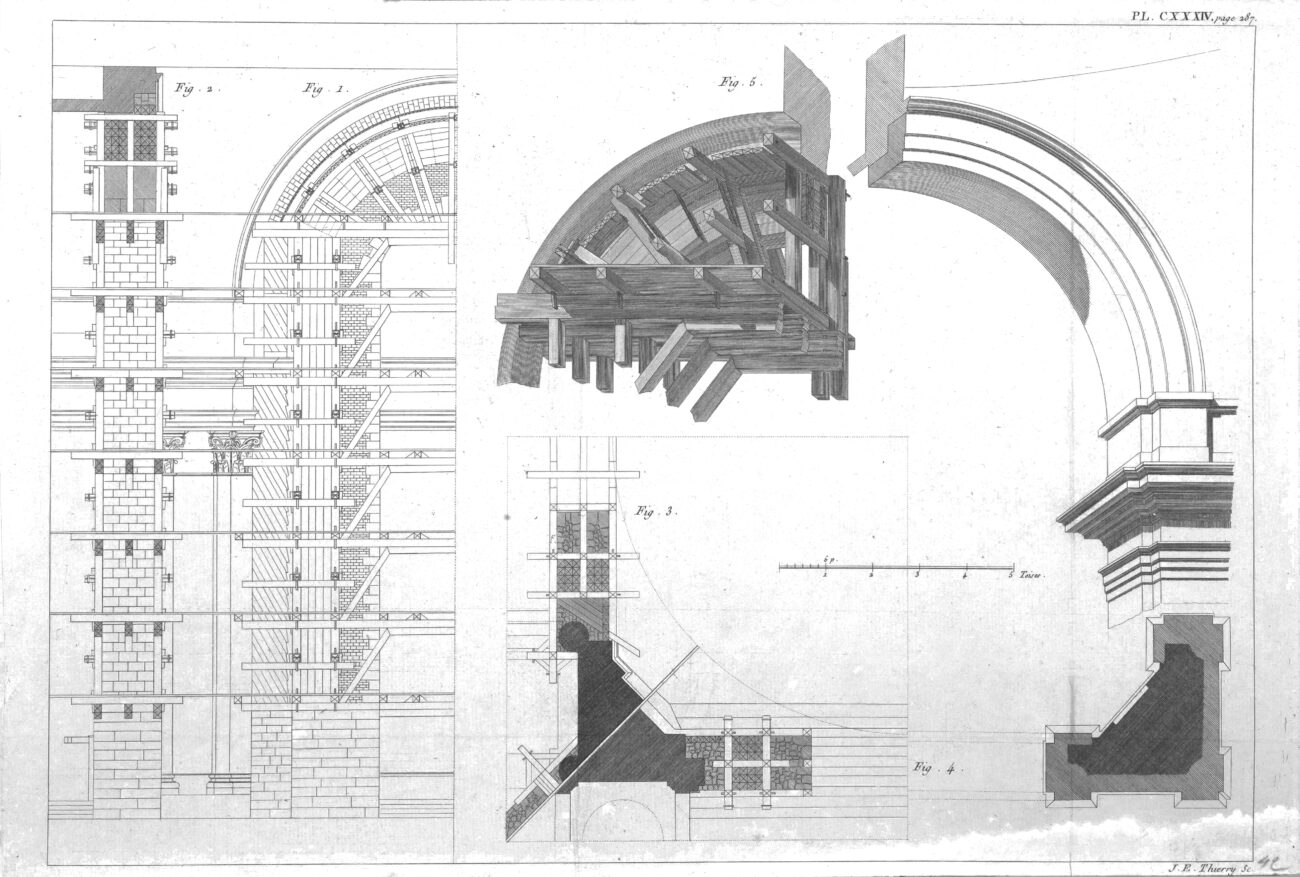

Architecture’s conceptualisation of matter has not been impermeable to these philosophical discourses. In spite of the negative reputation that the Aristotelian hylomorphism projected on matter by converting it into the reverential servant of form – absent in pre-Socrátic philosophy and being introduced, in different ways, by Plato and Aristotle – in the last centuries many architectural projects opposed this status quo by capitalising on both types of materialism. Since the Enlightenment and still under form’s reign, matter has been recovering its pre-Socratic positive character by absorbing all the attributes traditionally ascribed to form. However, it also operated a conceptual replacement that is crucial in this discussion: matter moved from a marginal role in a hylomorphic dualist scheme to the solitary leadership of an ultimate holism. As we will see below, in architecture and particularly since the Enlightenment, matter’s relevance has been gradually recovered through its association with two key concepts: truthfulness, emphasised by authors of the late 18th and 19th century such as Viollet le Duc or Gottfried Semper, and vitalism, underlined by authors of the 19th century and early 20th century such as Henry Bergson or Henri Focillon. Today this process has culminated with Eric Sadin’s notion of antrobology, that is, the “increasingly dense intertwining between organic bodies and ‘immaterial elfs’ (digital codes), that sketches a complex and singular composition which is determined to evolve continually, contributing to the instauration of a condition which is inextricably mixed ‘human/artificial.”

In this technological framework and through the notions of information, platform and performance, matter’s traditional attributes have been replaced by those of form. Despite keeping the term “matter” as a signifier, the disorder, passivity and homogeneity that conventionally characterised its significance have been substituted by form’s structure, activity and heterogeneity. However, one crucial feature that is absent in the dualistic hylomorphic model has been reintroduced: matter’s pre-Socratic condition of being ultimate.

This incorporation is decisive when it comes to architectural part-thinking. In spite of the great popularity that matter has achieved within contemporary experimental architecture, its ultimate condition precludes any engagement with architectural part-thinking: either as a single continuous field or as a set of discrete particles, matter exalts a single holistic medium that lies at the core of reality, that is, a fundamental substrata (whole) in which all specific entities (parts) can be reduced. In a context in which designers use the power of today’s super computation to notate the inherent discreteness of reality instead of reducing it to simplified mathematical formulas, or field, reality’s approach through generic and Euclidean points (particles) rather than distinct elements (parts) constitutes an unnecessary process of reduction that dissolves part’s autonomy.

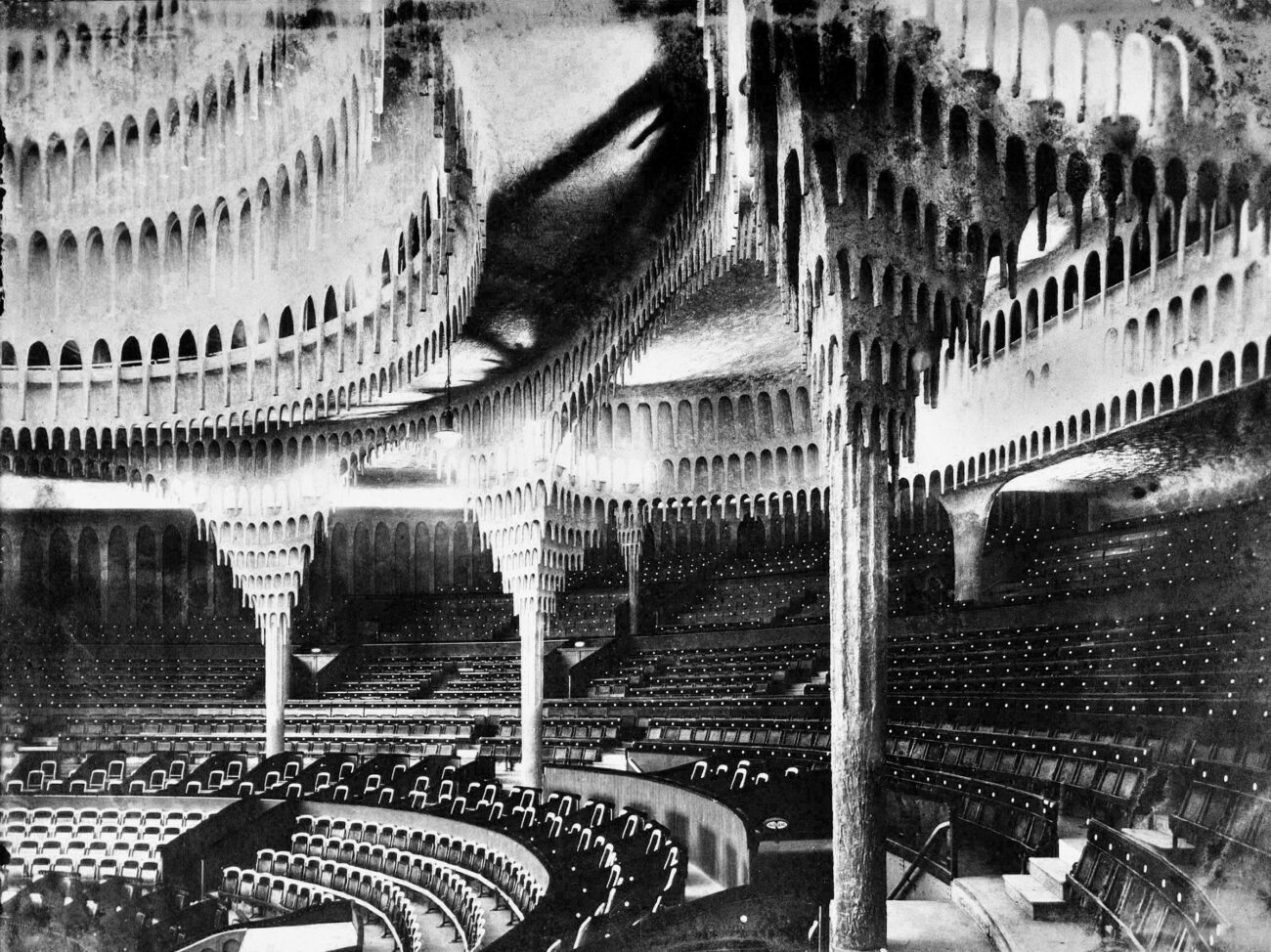

This essay develops this argument in two steps. First, it states that the current culmination of matter’s revival process in experimental architecture is, paradoxically, nothing but the exaltation of form; under the same signifier, matter’s signification has been replaced by form’s signification: all attributes that in the hylomorphic model were associated with the latter have now moved to the former, converting matter’s signifier into just another term to conjure up the significance of form. However, there is a crucial pre-Socratic introduction in relation to the hylomorphic model: matter is now understood as being also the ultimate single substance of reality, and not just the compliant serf of another element (form). This holistic vocation can be traced in contemporaneous experimental architecture in parallel to matter’s pre-Socratic distinction between a continuous field (Anaximander’s apeiron) and a discrete set of particles (Democritus’s atoms).

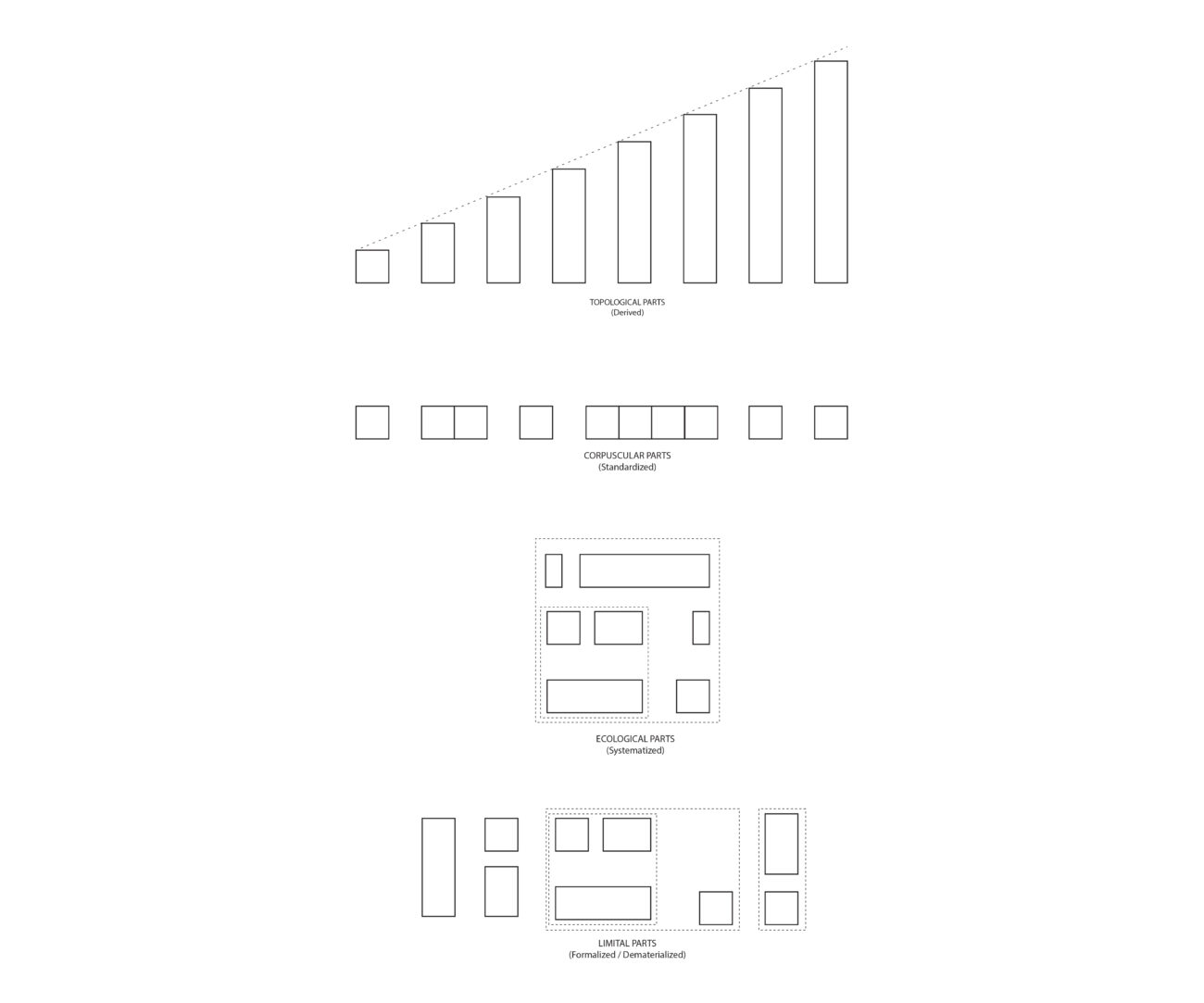

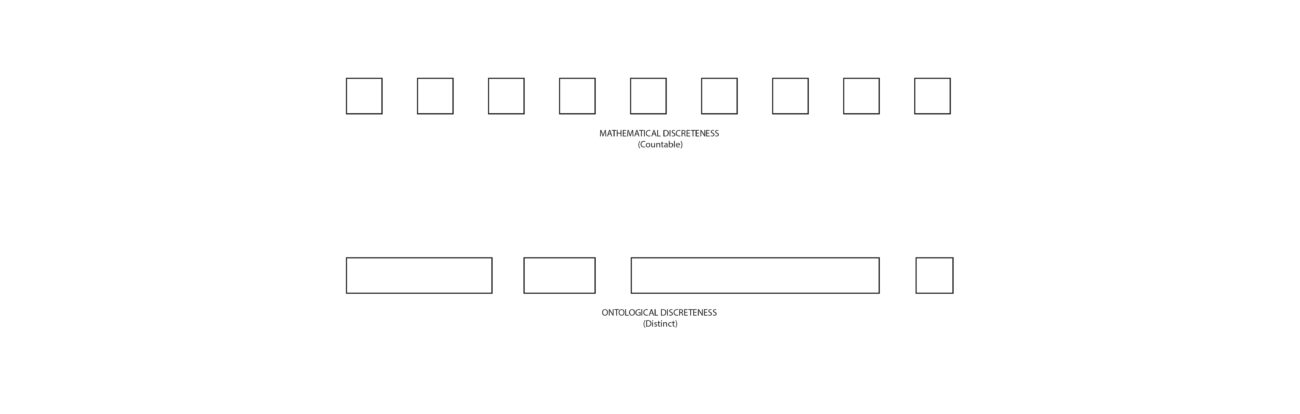

Second, this essay argues that current materialism, in any of its twofold registers, is incompatible with architectural part-thinking. The argument first identifies and evaluates three groups of architectural parts (topological, corpuscular and ecological) in the current experimental architectural landscape and second proposes a fourth speculative architectural part based on the notion of limit. If the idea of part demands a certain degree of autonomy from the whole, it cannot be reducible to any ultimate substrata, and therefore matter’s holistic condition becomes problematic both in its continuous and discrete register. However, the latter demands particular attention: discretism’s spatial countability might lead us to confuse the notion of particle with that of part. However, they significantly differ: while particles are discrete only from a mathematical perspective (countable), parts are discrete as well from an ontological perspective (distinct). Parts require at least both dimensions of discreteness in order to be considered autonomous from any exteriority, while simultaneously keeping its capacity to participate in it.

Architectural part-thinking demands then a radical formal approach. It requires a notion of form that operates at every level of scale, that is, an immaterialist model that recursively avoids any continuous (field) or discrete (particle) ultimate substrata in which parts could be reduced. This pan-formalism would imply then the presence of a form beyond any given form, understanding the term “form” as an autonomous Spatio-temporal structure.

G. Harman, “Materialism Is Not the Solution”, The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, 47 (2014), 95.

E. Prieto, La vida de la materia (Madrid: Ediciones Asimetricas, 2018), 28-102.

E. Sadin, La humanidad aumentada (Buenos Aires: La Caja Negra, 2013), 152.

M. Carpo, The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence (Cambrige: MIT Press, 2017), 71.