Co-authored with Manuel Gausa

Incipit

I

As we write, politics both in the Western and Eastern world are marked by wild eruptions of xenophobia, intolerance and misogyny, exacerbated concentrations of wealth, hate and racism, homophobia, private and corporate avarice, surveillance capitalism, willful obliviousness towards the persecution of minorities and fierce denials of climate change.

In light of these reactionary positions, a set of pro-democratic, antiracist and xeno-feminist counter-politics of direct action and mass protest is urgently needed. Architecture offers a powerful channel to provide not just an implacable opposition to fascist, neo-liberal and anti-democratic practices, but also a space to shape “fluid politics” such as gender-abolitionism, anti-naturalism or techno-materialism. The critical reflection and dissemination of innovative future-based architectural practices emphasizing this direction are crucial in an architectural scene whose corporate register is void of a radical political agenda transcending calligraphic gesticulations, computational mannerisms and solipsistic discourses.

II

This book has been simmering during several years in the cauldron of a knowledge in action. It has been forged through encounters with practitioners and researchers, experiences with artists, designers and students, conversations, transdisciplinary readings, polymorphic audiovisuals, presentations, openings, lectures, symposiums. A composite of sustained interactions that in the last years has crystallised in lectures, papers and interviews, and that now is articulated through the present book.

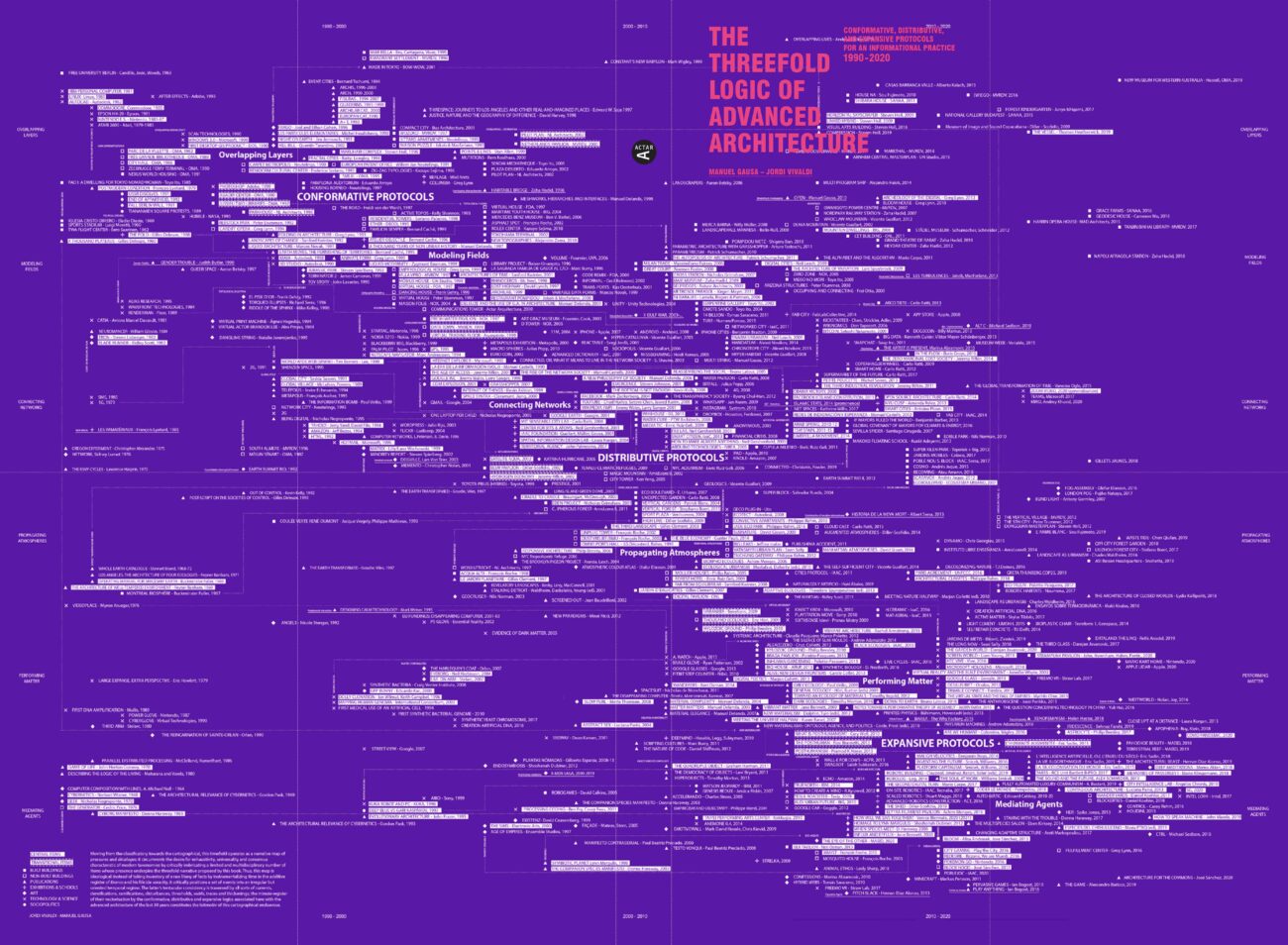

This work proposes a threefold cultural narrative whose interactive and informational nature differs from that of modern and postmodern logics. It positions three different ethos by critically approaching the architectural side of a cultural mutation that has been affecting the Western experimental areas of knowledge and practice since the end of the last century. A transformative process constituted by a constellation of transdisciplinary manifestations, accelerations, turns, shortcuts and clusterizations that by no means can be read under one single epistemological umbrella. In this sense, rather than approaching the practice of architecture focusing on its disciplinary inner specificity, this book approaches the research of experimental architecture focusing on its extra-disciplinary entanglements. It argues that a vast multiplicity of fields of knowledge participates in a cultural endeavour modulated through three protocols -forms of action- with a twofold particularity: first, its operative intensifications occur in three different decades, and, second, each protocol ramifies in a discrete and a continuous conjugation:

– Conformative Protocols stand out in the decade 1990-2000, operating under a discrete register based on “overlapping layers” and under a continuous register based on “modelling fields”.

– Distributive Protocols stand out in the decade 2000-2010, operating under a discrete register based on “connecting networks” and under a continuous register based on “propagating atmospheres”.

– Expansive Protocols stand out in the decade 2010-2020, operating under a discrete register based on “mediating agents” and under a continuous register based on “performing matter”.

These three protocols shouldn’t be read as three hermetic and concatenated monades, but as three different modulations of the same narrative; three modes of action that coexist during the last 30 years but whose peaks of intensity occur in 3 different decades.

However, the main purpose of this book is not limited to unveiling the ethos of these three conjugations. It aims also at using this framework as a “time-field”, a narrative map that moves from the classificatory to the cartographical in order to vectorize the last 30 years of experimental architecture. In this sense, this essay argues that this threefold set of protocols represents the progressive attempt to constitute critical interiorities “looking for” and “produced through” interactions that are increasingly more intimate and whose agents are increasingly more diverse. A tendency oriented towards the consolidation of an “intimacy between strangers” that highly resonates with the cultural and technological landscape in which experimental architecture operates.

The authorship of this book is twofold. It belongs to two complicit voices associated with two different generations. On the one side, Manuel Gausa, born on the cusp of the 60s and actively engaged with the architectural traffic between the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s. On the other side, Jordi Vivaldi, born on the cusp of the 90s and compromised with the philosophical and architectural production of the 21st century. The formation of both voices at the ETSAB in Barcelona and their subsequent involvement with the foundation and/or research of the IAAC (Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia) is not negligible since it defines a great part of the explorative gaze made in common.

The double nature of this authorship has an impact on the structure of this book. While the research is divided in three chapters that account for the three proposed periods, each one is articulated through the combination of two different formats: a long essay and a complementary corollary which are written by one author or the other according to his affinity with each period.

This research is firmly associated with the IAAC’s TAK area (Theory and Advanced Knowledge), directed by the authors. It represents the construction of a synthetic vision that by no means pretends to elaborate an exhaustive inventory. Instead, it conjures up a limited number of experimental projects and ideas whose mode of action indicates the emergence and consolidation of a new era in the experimental realm; a composite of open, tentacular and informational narratives firmly entangled with the 21st century and not exempt of political controversy. In spite of this contemporary focus, this research doesn’t ignore certain echoes coming from the classical worlds of the Renaissance, Enlightenment and Romanticism. It also reverberates with some of the postmodern revisions and, of course, with many of the ideological and technological transformations that the modern order inscribed in the 20th century, which, for better or worse, still resonate in our current experimental realm.

III

On December 17, 1903, more than a century ago, the Wright brothers’ plane took flight for the first time over the beaches of Kitty Hawk. At nearly the same time, The Great Train Robbery by Edwin S. Porter was being screened. It was the first film that explicitly revealed the depth of the frame and subjective editing.

Three years earlier, in 1900, Sigmund Freud had published The Interpretation of Dreams, opening the century with a new conception of the psyche and the world. Only two years later, in 1905, Albert Einstein published his fundamental article on the Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein confirmed the break with the former separated notions of space and time, and their definitive link within a new space-time characterized by relative positions.

One year later, in 1906, Henry Ford was getting the “Model T” ready, fostering mass mobility and assembly-line production while materializing Taylor’s efficiency techniques and William James’s pragmatic theories. And, finally, in 1907, Pablo Picasso finished “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, the painting that would identify “cubism”, i.e., the analytical division of the object and its fragmentation into multiple contrasting facets.

In barely five years there was a coincidence of decisive contributions destined to transform the scientific, technical and intellectual landscape left by the 19th century. The development of those advances would consolidate a new type of operative logic applied to the definition and construction of space.

The classic “symbolic” logic had been overcome and substituted by a more material, objective and pragmatic logic that was qualified as “modern”. Thus, modernity celebrated an apparently more rational – but no less deterministic – form of action arising from a new planimetric, relational and sequential vision of space. It operated through a notion of “mechanics” that was abstract in its form and serial in its production, associated with a positivistic – if not severe or “stripped down” – interpretation of reality itself.

IV

In the mid 20th century, decisive advances occurred simultaneously in different areas of knowledge. The 1960s witnessed the transmission of multiple images in space through the introduction of the television: the “monofocal” projected image of cinema’s big screen exploded into a myriad of small screens distributed in the territory. Real and virtual scenarios – and messages – started to coexist and overlap, a phenomena reflected by Marshall McLuhan in Understanding Media (1964) or Guy Debord in Société de l´espectacle (1964). Shortly thereafter, in 1969, the Internet was born – the first network, Arpanet – based on military and academic interfaces connecting different research centers.

In 1961, Murray Gell-Mann’s study of elemental particles and the computational development of quantum physics closely preceded the publication, in 1963, of Edward Lorenz’s text on non-periodic flows. The document had a decisive influence on chaos theory as well as on James Forrester’s 1969 definition of “dynamic systems”, whose application to the changeable understanding of nature was put forward by Benoît Mandelbrot in his studies of irregular geometries.

In resonance with these technical and scientific developments, the 1960s anticipated “liquid” conceptions of reality through theories such as Lacan’s works on ego and desire, Foucault’s structures of power or Deleuze’s conceptual folds. While the moon landing in 1969 evoked developmental optimism and the Situationists maps conjured up imaginative indiscipline, the crises post May 68 and the birth of environmental consciousness originated a twofold socio-political attitude: on the one side, a profound desire for transformation, and on the other side, a deep mistrust in the established system.

V

As some attentive observers have probably already sensed, the individual and global relevance of those contributions began to anticipate a new operational logic, opposing both the Prometeic “objectuality” of Modernity and the anti-heroic calligraphy of Post-Modernity. It is constituted as an informed and informational systematic of thinking particularly sensitive to complexity; permeable and impure, symbiotic, perverted, derived from a “multiple” and “multi-layered” perception that by no means can be essentialized through figurative gesticulations.

A logic based on diverse stimuli in mutual interaction, supported by “irregular” processes of change and exchange; interested in multitudes rather than in identities, in experimentation rather than in representation, in miscegenation rather than in domestication, in cartographies rather than in classifications, in plurification rather than in purification. It unfolds a spatial approach that replaces “relative positions” with “interactive dispositions”; a form of action favouring an approach to reality that is operative instead of pragmatic, immersed instead of transcendental. It incorporates unheard-of expressions that are transgressive and paradoxical, hybrid frameworks where the natural implies the synthetic, where the virtual overlaps the physical, where the systematic celebrates the exceptional.

Privileging the emergence of symbiotic pluralities over the design of refined identities reveals an architectural shift from static and figurative gestures towards effervescent and interactive frameworks. The consolidation of this turn has left its trace on the past three decades: its explorations, anticipations, falterings and transitions constitute a breeding ground for action shared by different avenues of investigation and, in particular, by the experimental architecture of the last decades.

The following book is dedicated to this collective adventure.