Curated by: Kory Bieg, Danelle Briscoe, and Clay Odom

In spite of some scattered references in Surrealist work – the empty streets in de Chirico’s paintings or the mysterious châteaux in Breton’s poetry, architecture does not immediately come to mind when Surrealism is evoked. (Tashjian 2005) The Surrealists associated buildings with the heaviness, monumentality and order that they wanted to subvert. The relation seems even more tenuous when technology is also conjured up: Surrealism was not interested in the positivism associated with scientific methods, technical systems or new materials because its hyper-rationality seemed to shade the multivalent meaning that lies beneath it. In the last decade, however, the generalisation of machine learning and robotisation has promoted a new computational intelligence that exceeds the 19th-century positivism despised by Surrealism, emphasising the centrality of “autonomy” and “ubiquity”. Eric Sadin defines this computational intelligence according to five points: autonomy, reasoning, learning, ubiquity and cooperation. (Sadin 2017) Some recent experimental architectural projects have integrated these advancements, receiving the name of second-order cybernetic architecture (SOCA) due to their capacity to act within the system they operate.

Although SOCA’s fabrication strategies and design methods have been largely discussed, this paper approach another side of this phenomenon which has received less attention: its aesthetic dimension – in particular, SOCA’s possible relation to Surrealism in keeping with Walter Benjamin’s notion of “distracted perception”. Approaching aesthetics as a mode of appropriation, Benjamin stated that “buildings are appropriated in a twofold manner: by use and by perception – or rather, by touch and sight.” (Benjamin 1935) This architectural appropriation is generally not understood through the attentive regard and far-off image of tourist’s optic vision (sight), but through the “distracted perception” and close-image of user’s haptic vision (touch). Rather than as a visual intermittent event, architecture’s perception is usually constituted as a haptic continuous habit that implies its aesthetic absorption by the user. According to Benjamin, “distracted perception” relates to the generalisation of mechanical reproduction techniques characteristic of the early 20th century. Cinema and photography represent not just the shift from the “auratic” to the “reproducible”, but also the consolidation of a mode of perception in a state of “distraction” rather than in a state of “concentration”.

This paper hypothesises that SOCA re-articulates Benjamin’s “distracted perception” through an aesthetic experience that is structurally Surrealist. Despite Surrealism’s coldness towards architecture and technology, this paper associates them through an argument that is threefold. First, it argues that the Surrealist primacy of presentation (index) over representation (icon) in relation to the unconscious is particularly manifested in SOCA through the notion of “performance”. Second, it argues that this presence is achieved, in both cases, through an automated technique that mediates reality in a non-human manner: by amplifying the human being, its displacement occurs. Third, it argues that the paradoxical conjunction of opposites achieved by Surrealism through its simultaneous articulation of closeness and distance is also present in SOCA, particularly through a concurrent production of empathy and alterity.

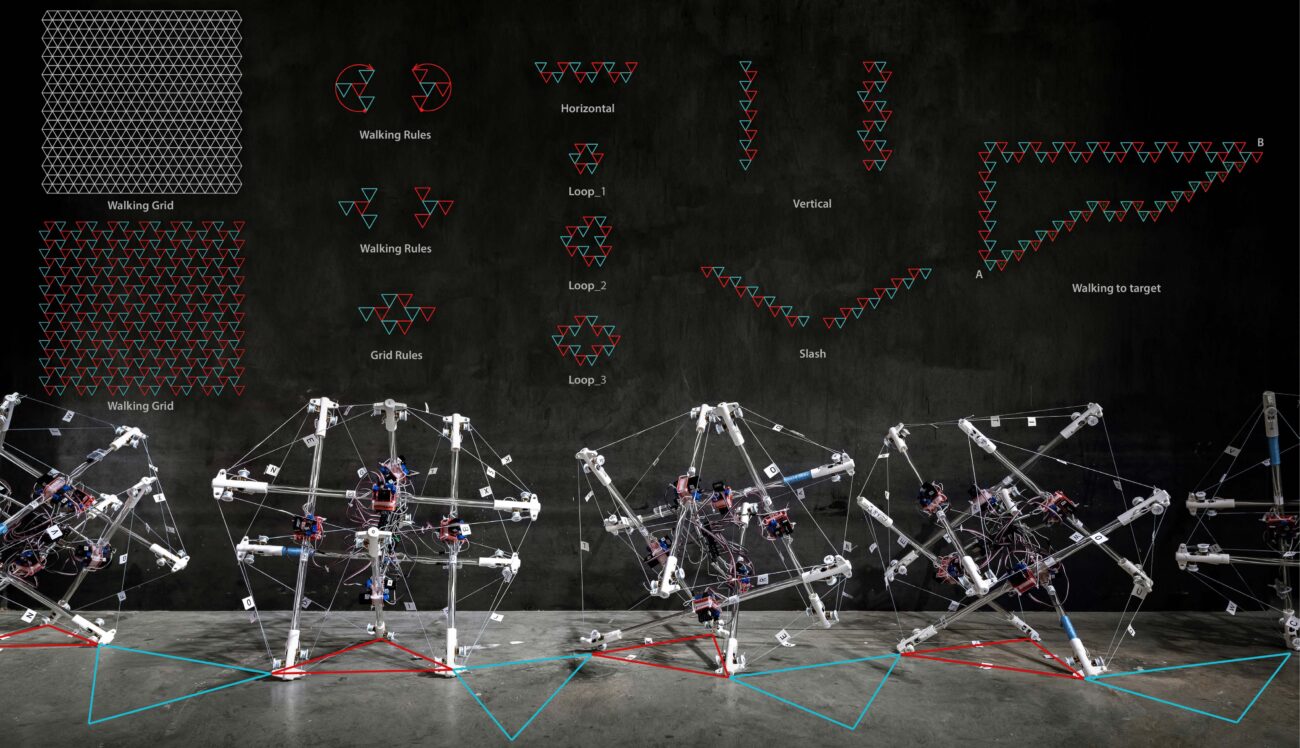

Each argument is doubly articulated: first it compares Surrealist artwork from the first half of the 20th century and three SOCA projects; second, it evaluates its impact on Benjamin’s “distracted perception”. Projects are chosen by virtue of their close relationship with Sadin’s aforementioned five points. First, Özel’s “Livef0rms” (2014), a robotically assembled modular system controlled by an adaptive algorithm that produces a pavilion and performance stage set for electronic music (Figure 4). Second, Bartlett RC3’s Living Architecture “TARSS” (2018), a fully automated series of tensegrity structures that are self-assembled through machine learning protocols in order to produce Martian dwellings (Figure 5). Third, Beesley’s “Hylozoig Ground” (2010), an artificial and responsive forest made of an intricate lattice of small transparent acrylic meshwork links, fitted with microprocessors and proximity sensors that react to human presence (Figures 1,6).

The evaluation of this exercise concludes that SOCA’s Surrealism replaces the inner and unconscious other characteristic of traditional Surrealism by an outer and algorithmic other that demands a significantly different theoretical background. In this sense, SOCA’s surrealism paradoxically expands and contracts at the same time Benjamin’s “distracted perception”. On the one hand, SOCA expands Benjamin’s notion through a performative, automatic and empathic accommodation to users’ needs, which highlights architecture’s perception as a continuous habit based on a close-up view. However, on the other hand, SOCA’s algorithmic autonomy contracts “distracted perception” by precluding any full aesthetic absorption from its user. In spite of SOCA’s hyper-accommodation to its inhabitants, there is always a remainder of otherness, absent in Benjamin’s architecture, which cannot be completely exhausted and which remains always unresolved. Paradoxically, both effects are perceived through the single framework of haptic vision.

In experimental academic architecture and over the past decade, the formal recourse to continuity, gener- alized with the computational revolution of the 1990s

In experimental academic architecture and over the past decade, the formal recourse to continuity, gener- alized with the computational revolution of the 1990s