Co-authored with Tiziano Derme, Daniela Mitterberger and Gonzalo Vaillo

Published in October 2020

External Link ↗︎The arrival of the notion of “Hyper-Communication” and its associated “Transparency Society” reveals a new Media Condition: an informational framework characterized by being carnal, recursive, omnipresent, immediate, intimate and exact. This optimized and embodied gaze constructs a pervasive communicative scenario that differs from the pre-digital era by a paradoxical fact: while the amount of information exposed has been massively expanded, the exposure time of each informational phenomena, particularly visual representations, has been considerably reduced. This resulted in a drastic decrease of the amount of time available for its cognition and the exhaustion of its Value-Information.

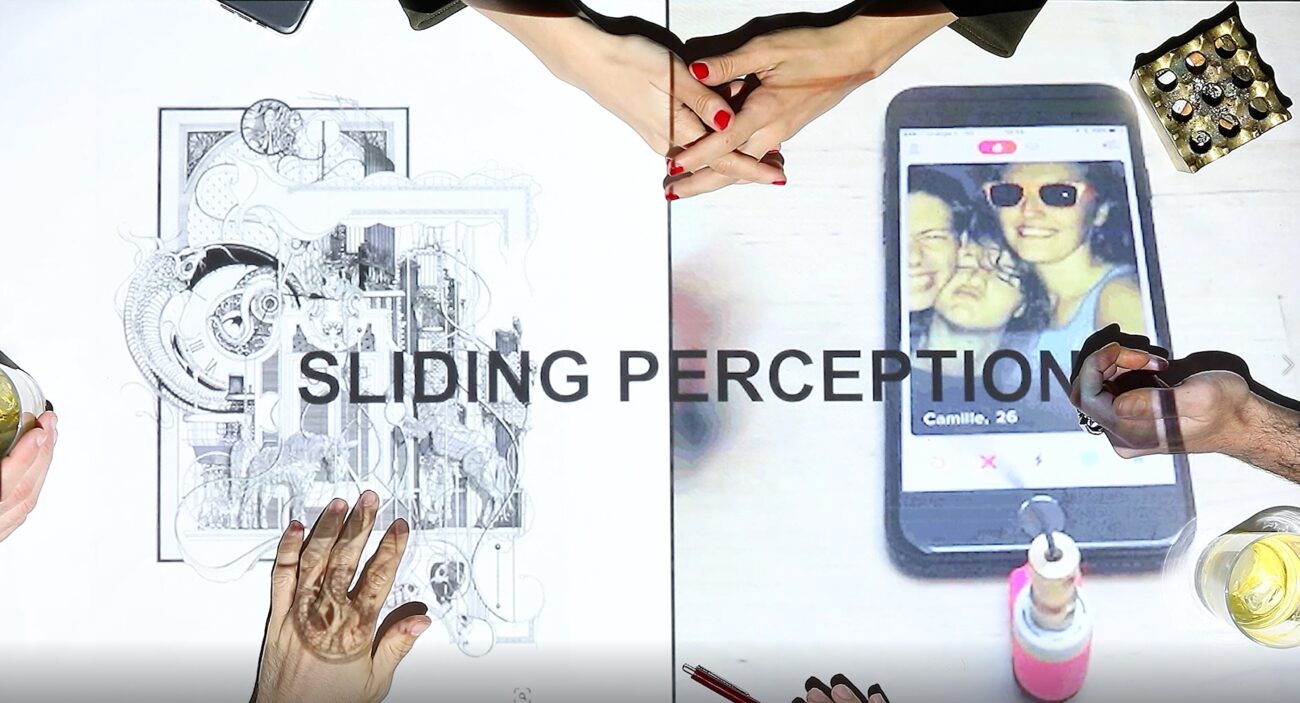

This cognitive framework responds to a 21st-century technological condition in which iterative algorithmic repetition has become the mode of production par excellence. The massive, immediate, embodied and ubiquitous proliferation of information characteristic of our age, widely celebrated -by themselves and in themselves- through our social networks, constructs a regime of sameness inaugurating a new form of sensibility: a perceptual condition defined here with the expression “sliding perception”. Rather than intermittent attention operating through discrete jumps and accumulations of ratios, sliding perception is, above all, a scrolled perception based on perpetual replacement and iterative substitution. It is constituted as a sensibility vertebrate by a frictionless and wandering attention: an elongate scrolling and an insistent deferral, an oscillating -almost ludic- dérive, always incomplete, always voracious, but, paradoxically, at the same time, always saturated, always flooded. Always doubting between the “enough” and the “more”, always alternating between the “tedious” and the “colorful”, sliding perception does not imply a mere de-sensibilization, but a re-sensibilization orchestrating a twofold action: the eye is being hipo-sensitized as a tool for sensing differentiation while is being hiper-sensitized as a tool for sensing repetition.

In this scenario, this text argues that to reveal the opportunities embedded within this techno-perceptive condition demands from us to delve into the concepts orbiting around the notion of copy, an approach already done by Hannah Arendt and Jacques Derrida with the notion of lie. Today, the old dichotomy “repetition – differentiation” dissolves into a myriad of derivatives associated with the former: replica, paraphrase, duplication, transcript, reproduction, mímesis, copy-paste, tweening, scanning, doubling, cloning, repetition, ditto, engraving, or facsimile emerge as the modes of production par excellence of the 21st century. Those mechanistic tendencies fall today into a new literacy and creative abilities based primarily on short span attention, recursive algorithms, databasing, data trailing, recycling, remixing, appropriation, intentional plagiarism, identity ciphering, intensive reprogramming… These actions are used as daily intensifiers shaking the notions of identity, media, and culture as they have been established by the industrial paradigm of the 20th century. Thus, the notion of “copy,” traditionally marginalised by the Western glorification of the idea of creation and its secularization through the modern myth of the tabula rasa, is redeemed: in the XXI century, copying, in its plethora of modulations, has the potential to fuel new modes of contribution. However, a question mark arises: How to produce difference in a regime of transparency? How to produce distinction in a regime of sameness? How to produce originality when there is no Patient-0? Under the regime of the algorithmic copy, the notion of originality demands reconsideration: rather than approaching what is original as what is distinct, the former must be read as what is originative. The original is no longer only what is necessarily different, disparate or divergent, but what originates: while what is distinct necessarily refers to the past in order to differ from it, what is fertile cannot but refer to the future in order to inseminate it.

Thus, the notion of copy exposed here opposes both its modern and postmodern equivalents: while modernism relies on the spatial copy of an optimised standard, postmodernism relies on the historical copy of a calligraphic gesture. However, in what specific way does the notion of algorithmic copy instrumentalized here differ from the one done by these two precedents? Is it in its computational nature? Is it in its autonomous vocation? Is it in its ubiquitous condition? Is it in the information’s increment or reduction characteristic of algorithmic copying processes? And, above all, how is this specificity associated with our technological scenario?

In this sense, Lyotard’s landmark exhibition “Les Immateriaux” foreshadowed a turning point: it prophesied a technological insurrection advocating for radical disembodiment, globalisation and an accelerated rate of information exchange. However, the fact that our body is still -maybe more than ever- intimately associated with immaterial technologies radically transforms the way we perceive and produce information: it opens the door to interactive processes whose immediacy and ubiquity might partially circumvent the moral, political and aesthetical filters associated with our consciousness. Thus, the Hyper-Communication society is, above all, an embodied society disrupting any unitarian conception of the notion of subject: it impacts our bodies emphasizing its relational, affective and transversal dimension; it constructs de-synchronised, kaleidoscopic and diffracted corporalities collaboratively linked to a material network of organic and non-organic beings. In light of this embedded scenario, a hybrid and mestizo techno-natural regime emerges: defined here with the expression carnal technologies, it capitalizes on one fact of crucial relevance in our cultural landscape: the recursive and intimate association between (in)organic bodies and digital agents.

The projection on this technological scenario of the algorithmic register of the notion of copy, together with all its associated terminological universe, aims at unveiling, understanding and contextualizing new logics of production: a set of modes of action linked to recursive protocols that are intimately interlaced to a massive and carnal management of data.

However, the centralization of the notion of copy in light of this technological context opens a bunch of questions: for example, does our celebration of “copy” cancel the value of creativity? Or, should we still produce originality? Can we produce originality? Is the notion of newness intrinsically implying a modern attitude towards design? And, above all, can a copy, in the foliated structure characteristic of its algorithmic register, be a critical contribution?

The thinker Byung-Chul Han posits the notion of transparency as a false ideal in contemporary society. According to him, things presented without singularity or depth are “transparent” and are only governed by the “exhibition value,” posing no meaning at all. See Byung-Chul Han, The Transparency Society (2012; repr., Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015). Our approach takes Han’s concept neither as an endemic condition of the current technological age that denigrates the old romantic and contemplative social dynamics nor as technological positivism, but as an opportunity to reconsider the value systems, categorizations and beliefs within the already-established regime of hyper-information and hyper-communication.

See Jean Baudrillard – Simulacra and Simulation- The implosion of meaning in the media ( Éditions Galilée & Semiotext(e),1981)

See Eric Sadin, L’ Humanité Augmentée (Paris: Editions L’ échappée, 2013).

See Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (New York City, NY: Columbia University Press, 2011).

This idea relates with Conrad Fiedler’s theory of pure visibility. As Lambert Wiesing comments: “Pure visibility takes the substance away from the visibility of something. It is not bound up with any object, and does not refer to the presence of any entity. To speak phenomenologically, pure visibility has no intentionality, which is to say it is not the visibility of something.” See Lambert Wiesing, The Visibility of the Image: History and Perspectives of Formal Aesthetics (1997; repr., London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), chap. 4.