Ph.D Dissertation

Supervised by Peter Trummer

Introduction

Architecture is a critical cultural discipline. It problematizes how society interprets its own contemporaneity, thus defining itself as a body of knowledge. As a result, architecture is inevitably confronted to a particular ‘zeitgeist’ and the understanding of the subject that results from it. However, as is the case with any content, architecture needs a form for its transmission. In contrast to other disciplines such as music, literature, philosophy, mathematics, sculpture or painting, architecture is set apart because it involves a unique formal operation: the introduction of a world within a world – in other words, the production of interiority. As a diachronic discipline, architecture develops the aforementioned formal singularity historically through a specific process: the re-articulation of parts within a gravitational scenario. This re-articulation necessarily occurs under the presence of a particular zeitgeist, pivoting between two formal extremes: a total independence of the parts, characteristic of a discrete framework; and a total co-dependence of the parts, characteristic of a continuous framework. As a critical mechanism for the production of interiority, the tension between discrete and continuous emerges as a unique, fundamental issue that belongs to the body of knowledge specific to architecture. In that sense, a set of questions emerges: By what methods do the discrete and the continuous produce interiority? How do they problematize a particular zeitgeist? What kind of knowledge is used to articulate both categories architecturally?

1.1 The Problem of the Floor and its Disciplinary Relevance

This dissertation frames the aforementioned debate in the context of a particular architectural element: the floor and its vertical layout. The singularity of the floor as part of an architectural whole is derived from the fact that, in contrast to other parts like walls, windows, pillars, or stairs, the floor is a necessary condition for the production of any kind of interiority within a gravitational scenario. Its absence is inconceivable. Along those lines, these pages will articulate the problematic as follows: what do the categories of discretism and continuity mean in the layout of the floor at height? How the articulation of each of these categories problematize our zeitgeist? What typologies of architectural production do they belong to? And, more specifically, how can the floor layout debate our subject’s understanding through a formal rearticulation of the discrete and the continuous? The relevance of this research is tied to a question that is rooted in our times but has seldom been addressed with the attention it deserves. It focuses on the possibility of a typology of disciplinary production based on the sameness of the architectural object. Where Vidler distinguished three typologies of architectural production based respectively on nature, technology and the city, in the cultural landscape of the 21st century the following question arises: is it possible to find a fourth typology based exclusively on the object? The question of the object has emerged over the past decade as an essential element in understanding the contemporary cultural landscape. In that sense, the advent of Speculative Realism in the early 21st century, and Object-Oriented Ontology in particular, has eliminated the idea of subject entirely, substituting the fields and ontological systems characteristic of the late 20th century with flat collections of objects that engender the Zero Subject. At the same time, in the last decade, and coming from the most experimental areas of architectural scholarship, there has been a certain exhaustion of an architectural rhetoric and aesthetics based on continuity. Exalted in the 1990s from digital parametricism, its continued use over the years has transformed it into a banality with very limited disciplinary interest. In its place, some academic circles have recently experimented with a return to a discrete formal vocabulary, although its impact has been largely cosmetic up to now. The problem of the floor is very well suited to bring about a qualitative increase in the scope of that impact. The reason lies in the performative and necessary nature of its presence: the floor can hardly be reduced to a mere contingency whose value is accidental. On the contrary: the layout of the floor tends to go unnoticed; it is not made an issue because its presence is so essential that it is accepted acritically as a given. However, its participation as diagram is fundamental: the layout of the floor does not qualify space only through formal categories, but also through performative ones given its peculiarity of being in constant contact with us. This work will approach two main floor diagrams: the discrete floor, represented by the skyscraper, and the continous floor, represented by the topological slab of the end of XX century. In that context, the following question arises: is it possible to produce a new diagram in the vertical layout of floors? How would it problematize the current zeitgeist? And, above all, how would that diagram rearticulate the concepts of discrete and continuous as they are formulated by the other two diagrams? In response to these questions, this dissertation proposes a new floor layout: the continuous while discrete floor. Based on a comparative analysis, this research concludes that the disciplinary originality of this floor type and its complicity with the contemporary cultural landscape are part of a fourth typology of architectural production: the object-based typology.

1.2 The Method

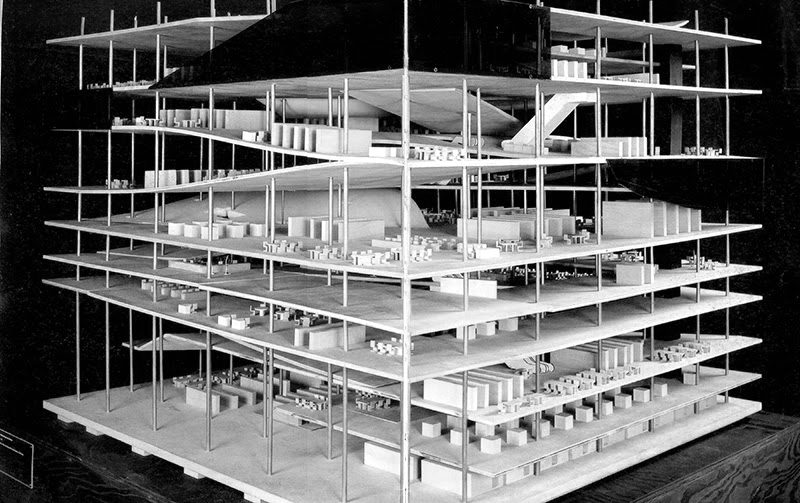

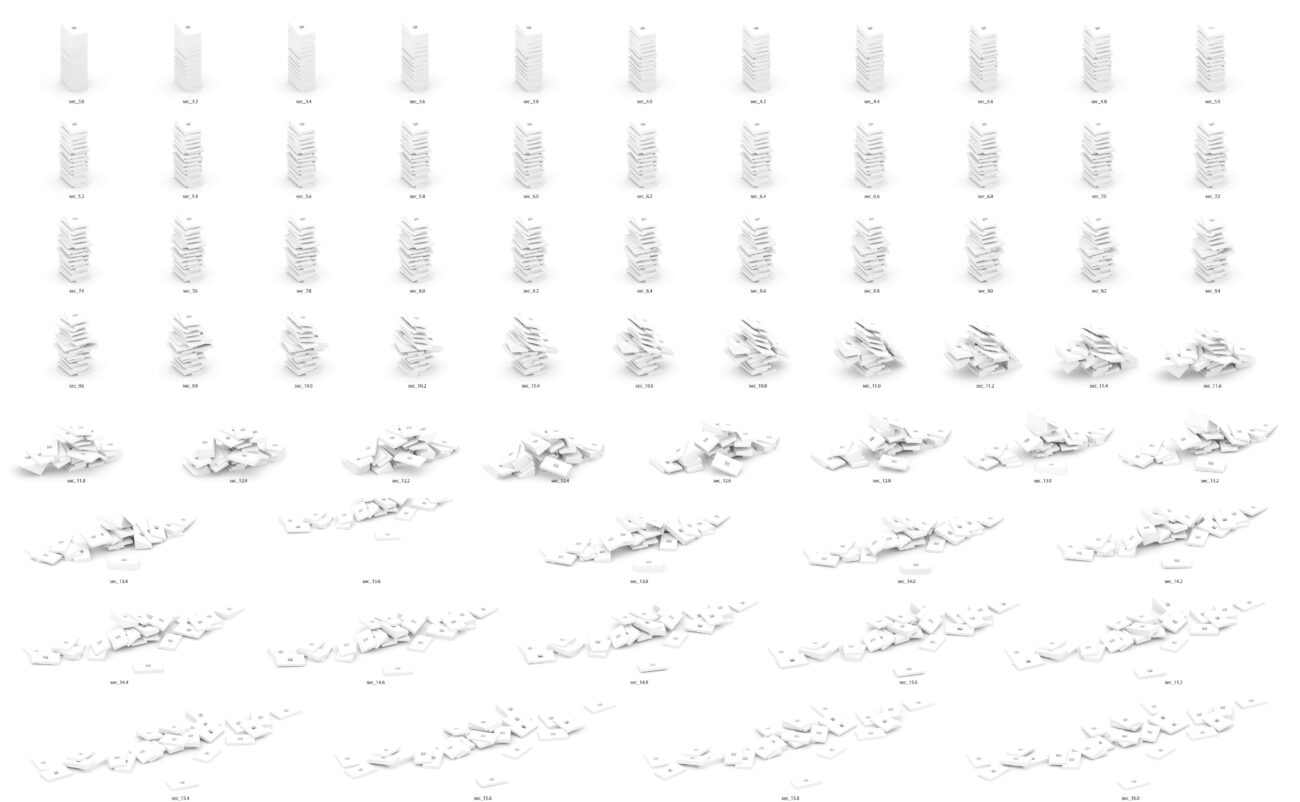

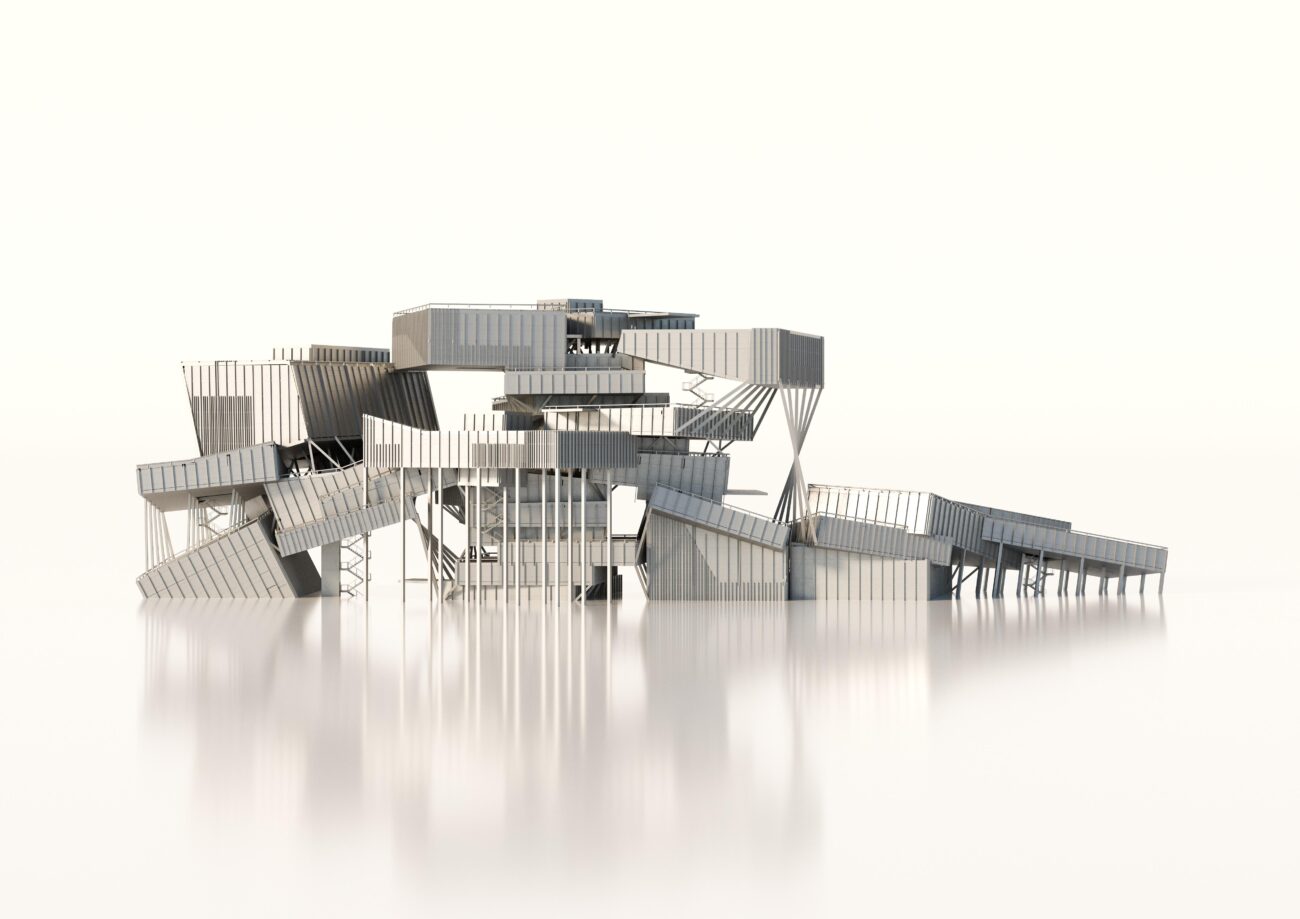

In order to reach this conclusion, the author will employ an analytical method and a design method. The analytical method, focused on the floor layout, consists in the compilation of a comparative table. This table associates two particular interpretations of the subject with two floor layouts: the discrete layout – the quintessential example of which is the skyscraper, is associated with the absolute subject characteristic of modernity; and the continuous layout – the quintessential example of which is the topography-building, is associated with the relational subject characteristic of post-modernity. Each period’s interpretation of the subject provides a definition of its particular zeitgeist. To that end, this research will analyze who functions as a subject, the subject’s position in the world, and how that subject relates to objects. This ontological understanding of the subject gives rise to an epistemology framed within a particular school of thought. In that context, this dissertation will highlight, respectively, one philosopher who deals with the ontology of the subject and another who focuses on its social consequences. The layout of the floor will be analyzed from four points of view. First, by studying how the concepts of continuous and discrete are articulated. Second, by analyzing six formal spatial qualities that are relevant in their comparison: mereology, geometry, outline, arrangement, development and figuration. Third, by analyzing six performative spatial qualities that are relevant in their comparison: circulation, point of view, orientation, privacy, interiority, and access. Fourth, and finally, by studying the type of spatiality in which they are embedded, drawing on Eisenman’s distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous space. Each floor layout forms a specific diagram. That diagram gives rise to a large variety of designs, from which a single case study will be chosen to represent each layout. This table will also serve to evaluate how the proposed disposition of floors can be qualified as original in disciplinary terms based on the two cases studies. It will also be useful when it comes to revealing the complicities between the floor layout and our contemporary conception of the subject. The design method consists in the preparation, execution and analysis of a computation exercise that simulates a resonant piling, that is to say, a piling process in which its elements are able to produce formal intertwinings under certain circumstances. Through its materialization in a sequence of three-dimensional models, the simulation results in a unique rearticulation of the slabs from the discrete floor layout. First off, this method is in keeping with the understanding of architecture that underlies this research: it proceeds on the basis of parts and operatively assumes the fact of gravity. Second, it problematizes the contemporary conception of the subject: it works only with collections of objects, highlighting their ex-centric condition and providing for a particular type of interweavings. Finally, the results are analyzed based on a graphic catalog made up of six categories, whose inclusion is fundamental to explaining the contributions of the ensemble: Clumps, Distributions, Fillings, Interstitialities, Silhouettes and Grounds. Each of these categories analyzes a series of specific cases according to four main aspects: Generation, Form, Performance and Subjectlessness. This four-part approach ensures a proper understanding of how the model is created, its formal and performative singularities, and how it establishes complicity with subjectlessness.

1.3 Structure of the Research

This dissertation is divided into six chapters, being the first one its introduction. Given that this investigation is a formal study focused on the discrete and the continuous, the second chapter is dedicated to introducing those two concepts. Then, following the method of analysis described above, the discrete floor and continuous floor are described in the light of the absolute subject and the relational subject, respectively. An intermediate case between the two is described in less detail: the discrete and continuous floor. The third chapter describes the advent of the subjectless object in the contemporary cultural panorama. In addition, a state of the art is also presented from a critical perspective, highlighting the strictly cosmetic value of most of the architectural designs that are mentioned. This chapter concludes with the articulation of the hypothesis that structures this dissertation. The fourth chapter presents a description of and the arguments to support the design method used: resonant piling. On the one hand, it is worth differentiating this method from other emergentist design methods; on the other, it is clarified based on three concepts characteristic of the Zero Subject: collections, ex-centricities and interweavings. The fifth chapter analyzes the results of the simulation, evaluating the formal originality and performativity of the proposed floor layout. It also describes how the concepts of discrete and continuous can be reinterpreted in relation to the type of spatiality that is obtained. The dissertation concludes with chapter sixth, returning to the initial question of a fourth typology based on the object and linked to the proposal of the ‘continuous while discrete’ floor type. Here, a third diagram is proposed. It is no longer organized according to an emphasis on the discrete at the expense of the continuous or vice versa, but rather, as will be apparent throughout this dissertation, on the basis of an aporia: the continuous while discrete floor is continuous because it is discrete, and it is discrete because it is continuous. A relationship of necessity is established between the two notions which, when applied to the problem of the floor, results in both formal and performative originality. As such, the fourth typology emerges as a tool for architectural production that simultaneously generates disciplinary novelty while also problematizing our contemporary context from a critical perspective.

“To escape such a dependence on the zeitgeist – that is, the idea that the purpose of an architectural style is to embody the spirit of its age – it is necessary to propose an alternative idea of architecture, one whereby it is no longer the purpose of architecture, but its inevitability, to express its own time.”

Peter Eisenman, “The End of the Classical: The End of the Beginning, the End of the End,” in Architecture Theory since 1968, ed. Michael Hays, (New York: Columbia Books of Architecture, 2000), 529.

The term “form” should be understood in the way it is used by Tristan Garcia. According to the French thinker, form is the negative of an object – that is, everything that contains it, on the one hand adapting to its profile and, on the other, stretching out into infinity: “Form is what connects the infinite plurality of things to an identical formal infinity.”

Tristan Garcia, Form and Object, ed. Graham Harman, trans. Mark Allan Ohm and Jon Cogburn (Paris: Edinburgh University Press), 2014, 144.

Peter Trummer, interview by Luca de Giorgi, “Peter Trummer: What is Architecture,” July 12, 2013, in What is architecture?, produced by whatisarchitecture.

cc, video 00:11:03, accessed June 8, 2018, https://vimeo.com/70166958.

It is interesting to observe how, at both extremes, the term ‘part’ loses the independent balance that differentiates it. Toward the discrete extreme, its absolute independence makes it into a whole; toward the continuous extreme, its absolute surrender to the whole totalizes it.

The term “typology” should be understood in the sense in which it is used by Anthony Vidler in his seminal article “The Third Typology”.

Anthony Vidler, “The Third Typology,” in Architecture Theory since 1968, ed.

Michael Hays, (New York: Columbia Books of Architecture, 2000), 288-94.

The singularity of that kind of typology would reside in that fact that, while in the three prior typologies the referent is always located outside the architectural object – whether in nature, technology or the city – in the fourth typology the referent is located within the object itself.

Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman, “Towards a Speculative Philosophy” in The Speculative Turn, ed. Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham

Harman (Melbourne: re.press, 2011), 14.

“We humans are objects. The thing called a ‘subject’ is an object. Sentient beings are objects. Notice that ‘object’ here doesn’t mean something that is automatically apprehended by a subject.”

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects (London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 149.

Together with the hammer, the floor is one of the most common examples that is used in order to explain the Heideggerian concep of “readiness-to-hand” (Zuhandenheit). Readiness-to-hand is manifested in its purest form when the user uses the tool without thinking about the tool at all, which is precisely the case of the floor.

Peter Eisenman, Palladio Virtuel, (London: Yale University Press, 2015), 10.